Introduction

I had interview for the Flask book recently and some questions were related to realtime functionality - how it works, how to integrate realtime portion with conventional WSGI applications, how to structure application code and so on.

We used Google Hangouts and it was supposed to record interview, but it failed. So, I decided to write elaborate blog post instead, in which I will try to cover basics, give short introduction into asynchronous programming in Python, etc.

Little Bit of Theory

Lets try to solve server "push" problem. Web is all about pulling data - browser makes request to the server, server generates and sends response back. But what if there's need to push data to the browser?

Solution is simple: browser makes AJAX request to the server and asks for updates. While it seems like what's usually happening between browser and server, there's a catch. If server does not have anything to send, it will keep connection open until some data is available for the client. After client received the response, it will make another request to get more data.

This technique is called long-polling.

Obviously, this is not very efficient approach. Noise to signal ratio is very high in most of the cases - it takes longer to process HTTP request (parse and validate headers, for example) than to send actual payload to the client.

But, unfortunately, it is most compatible way to push data to the client right now.

HTTP/1.1 improved situation a bit. TCP connection can be controlled by Keep-Alive header and, by default, connection will be kept open after serving request. This feature improved long-polling latency, as there's no need to reopen TCP connection for each polling request.

HTTP/1.1 also introduced chunked transfer encoding. It allows breaking response into smaller chunks and send them to the client immediately, without finishing HTTP request.

Unfortunately, there are incompatible proxies that attempt to cache whole response before sending it further, so client won't receive anything until proxy decided that HTTP request was complete. While it is sort of OK for "normal" Web - client will still get response from the server, but it breaks whole idea of using chunked transfer encoding for any kind of real-time purposes.

In September 2006, Opera Software implemented experimental Server-Sent Events feature for its browser. While SSE behavior is very similar to chunked transfer encoding, protocol is different and has better client-side API.

SSE was approved by WHATWG on April 23, 2009 and supported by almost all modern desktop browsers (except of Internet Explorer). You can see compatibility chart here.

There are other techniques as well, like forever-iframe which is one of two possible ways to do cross-domain push for Internet Explorer versions less than 8 (another one is jsonp-polling)s, HTMLFile, etc.

As a whole, all these HTTP-based fallbacks go under Comet name.

Lets see pros and cons of these approaches:

- Long-polling is expensive, but very compatible;

- Chunked transfer encoding is more efficient, but there's chance that it won't work for all clients and there's no way to know about it without some sort of probing;

- SSE is efficient as well, but not supported by all browsers. Good thing though - there's way to know if it is supported or not before establishing connection;

But all these approaches share one problem: they provide ways to push data from the server to the client, but to establish bidirectional communication, client will have to make AJAX request to the server every time it wants to send some data. This increases latency and creates extra load on the server.

Meet WebSockets

While WebSockets are not really new technology, but specification went through few incompatible iterations and finally was accepted in form of RFC 6455.

In a nutshell, WebSocket is bidirectional connection between server and client over established TCP connection. Connection is established using HTTP-compatible handshake (with additional WebSocket-related headers) and has additional protocol-level framing, so it is more than just a raw TCP connection opened from the browser.

Biggest problem of the WebSocket protocol is support by browsers, firewalls, proxies and anti-viruses.

Here is browser compatibility chart.

Corporate firewalls and proxies usually block WebSocket connections for various reasons.

Some proxies can't handle WebSocket connection over port 80 - they think it is generic HTTP request and attempt to cache it. Anti-viruses that have HTTP scanning component were caught doing this.

Anyway, WebSocket is best way to establish bidirectional communication between client and server, but can not be used as single solution to the push problem.

Use Cases

Keeping everything above in mind, if your application mostly pushes data from the server, HTTP-based transports will work just fine.

However, if browser supports WebSocket transport and WebSocket connection can be established, it is better to use it instead.

To summarize, best approach is: try to open WebSocket connection first and if it fails - try to fall back to one of the HTTP-based transports. It is also possible to "upgrade" connection - start with long-polling and try to establish WebSocket connection in background. If it succeeds, switch to WebSocket connection. While this approach might reduce initial connection time, but it requires careful server-side implementation to avoid any race conditions when switching between connections.

Polyfill Libraries

Luckily enough, there's no need to implement everything by yourself. It is very hard to work around all known browser, proxy and firewall quirks, especially when starting from scratch. People invested years of work into making their solutions as stable as possible.

There are some polyfill libraries, like SockJS, Socket.IO, Faye and some others, that implement WebSocket-like API on top of variety of different transport implementations.

While they differ by exposed server and client API, they share common idea: use best transport possible in given circumstances and provide consistent API on the server side.

For example, if browser supports WebSocket protocol, polyfill library will try to establish WebSocket connection. If it fails, they will fall-back to next best transport and so on. Engine.IO uses slightly different approach - it establishes long-polling connection first and attempts to upgrade to WebSocket in background.

In any case - these libraries will try to establish logical bidirectional connection to the server using best available transport.

Unfortunately, I had poor experience with Socket.IO 0.8.x, and use sockjs-tornado for my projects, even though I wrote TornadIO2 - Socket.IO server implementation on top of Tornado framework earlier.

Server Side

Lets go back to the Python.

Unfortunately, WSGI-based servers can not be used to create realtime applications, as WSGI protocol is synchronous. WSGI server can handle only one request at a time.

Lets check long-polling transport again:

- Client opens HTTP connection to the server to get more data

- No data available, server has to keep connection open and wait for data to send

- Because server can't process any other requests, everything is blocked

In pseudo-code it'll look like this:

def handle_request(request):

data = get_more_data(request)

return send_response(data)If get_more_data blocks, whole server is blocked and can't process requests anymore.

Sure, it is possible to create thread per request, but it is very inefficient.

While there are some workarounds (like approach described by Armin Ronacher), variation of which will be discussed later, asynchronous execution models fit this task better.

In asynchronous execution model, server still processes requests sequentially and in one thread, but can transfer control to another request handler when there's nothing to do.

In this case, long-polling transport will look like:

- Client opens HTTP connection to the server to get more data

- No data is available, server keeps TCP connection open and does something else in meanwhile

- When there's data to send, server sends it and closes the connection

Greenlets

There are two ways to write asynchronous code in Python:

- Using coroutines (also known as greenlets)

- Using callbacks

In a nutshell, greenlets allow you to write functions that can pause their execution in the middle and then continue their execution later.

Greenlet implementation was back-ported to CPython from Stackless Python. While it might seem that CPython with greenlet module is same as Stackless Python - it is not the case. Stackless Python has two modes of context switching: soft and hard. Soft switching involves switching python application stack (pointer swap, fast and easy) and hard switching requires stack slicing (slower and error prone). Greenlet is basically port of the Stackless hard-switching mode.

Lets check long-polling example again, but with help of greenlets:

- Client opens HTTP connection to the server to get more data

- Server spawns new greenlet that will be used to handle long-polling logic

- There's no data to send, greenlet starts sleeping, effectively pausing currently executing function

- When there's something to send, greenlet wakes up, sends data and closes connection

In pseudo-code, it looks exactly the same as synchronous version:

def handle_request(request):

# If there's no data available, greenlet will sleep

# and execution will be transferred to another greenlet

data = get_more_data(request)

return make_response(data)Why is greenlets are great? Because they allow writing asynchronous code in synchronous fashion. They allow using existing, synchronous libraries asynchronously. Context switching magic is hidden by greenlet implementation.

Gevent is excellent example of what can be achieved with greenlets. This framework patches Python standard library to enable asynchronous IO (Input-Output) and makes all code asynchronous without explicit context switching.

On other hand, greenlet implementation for CPython is quite scary.

Each coroutine has its own stack. CPython uses unmanaged stack for Python applications and when Python program runs, stack looks like lasagna - interpreter data mixed with native modules data, mixed with Python application data and everything is layered in random order. It is quite hard to preserve stack trace in such case and do painless context switching between coroutines, as it is hard to predict what is on the stack.

Greenlet attempts to overcome the limitation by copying part of the stack to the heap and back. While it works for most of the cases, but any untested 3rd party library with native extension might create bizarre bugs like stack or heap corruption.

Code that uses greenlets also does not like threads. It is somewhat easier to create deadlock when code is not expecting that function that was just called pauses greenlet and caller didn't have chance to release the lock.

Callbacks

Another way to do context switching is to use callbacks. Long-polling example:

- Client opens HTTP connection to the server to get more data

- Server sees that there's no data to send

- Server waits for data and passes callback function that should be called when there's data available

- Server sends response from the callback function and closes connection

In pseudo-code:

def handle_request(request):

get_more_data(request, callback=on_data)

def on_data(request):

send_response(request, make_response(data))As you can see, while work-flow is similar, code structure is somewhat different.

Unfortunately, callbacks are not very intuitive and it is nightmare to debug large callback-based applications. Plus, it is hard to make existing "blocking" libraries to work properly with asynchronous application without either rewriting them or using some sort of thread pool. For example, Motor, asynchronous MongoDB driver for Tornado uses hybrid approach - it wraps IO with greenlets, but exposes Tornado-compatible asynchronous API.

Futures

There are different ways to improve situation with callbacks:

- Using futures

- Using generators

What is future? First of all, future is a return value from a function and it is an object that has few properties:

- State of the function execution (idling, running, stopped, etc)

- Return value (might be empty if function is not yet executed)

- Various methods: cancel() to prevent execution, add_done_callback method to register callback function when bound function finishes its execution, etc.

You can check this excellent blog post, which compares promises to callbacks and why they're better than plain callbacks for writing better asynchronous code.

Generators

Python generators can be also used to make asynchronous programmers little bit happier. Long-polling example again, but with help of generators (please note, return from generators is allowed starting from Python 3.3):

@coroutine

def handle_request(request):

data = yield get_more_data(request)

return make_response(data)As you can see, generators allow writing asynchronous code in sort-of synchronous fashion. Check PEP 342 for more information.

Biggest problem with generators: programmer should know if function is asynchronous or not before calling it.

Consider following example:

@coroutine

def get_mode_data(request):

data = yield make_db_query(request.user_id)

return data

def process_request(request):

data = get_more_data(request)

return dataThis code won't work as expected, as calling generator function in python returns generator object without executing body of the function. In this case, process_request should be also made asynchronous (wrapped with coroutine decorator) and should yield from get_more_data. Another way - use framework capabilities to run asynchronous function (like passing callback or adding callback to Future).

Another problem - if there's need to make existing function asynchronous, all its callers should be updated as well.

Summary

Greenlets make everything "easy" at cost of possible issues and allow implicit context switching.

Code with callbacks is a mess. Futures improve situation. Generators make code easier to read.

It appears that "official" way to write asynchronous applications in Python would be to use callbacks/futures/generators and not greenlets. See PEP 3156.

Sure, nothing will prevent you from using greenlet-based frameworks at all. Having choice is a good thing.

I prefer explicit context switching and little bit cautious of greenlets after spending several nights with gdb in production environment figuring out strange interpreter crashes.

Asynchronous Frameworks

In most of the cases, there's no need to write own asynchronous network layer and better to use existing framework. I won't list all Python asynchronous frameworks here, only ones I worked with, so no offense.

Gevent is nice, makes writing asynchronous easy, but I had problems with greenlets as mentioned above.

Twisted is oldest asynchronous framework and is actively maintained even now. My personal feelings about it are quite mixed: complex, non PEP8, hard to learn.

Tornado is the framework I stopped on. There are few reasons why:

- Fast

- Predictable

- Pythonic

- Relatively small

- Actively developed

- Source code is easy to read and understand

Tornado is not as big as Twisted and does not have asynchronous ports of some libraries (mostly DB related), but ships with Twisted reactor, so it is possible to use modules written for Twisted on top of Tornado.

I'll use Tornado for all examples going forward, but I'm pretty sure that similar abstractions are available for other frameworks as well.

Tornado

Tornado architecture is pretty simple. There's main loop (called IOLoop). IOLoop checks for IO events on sockets, file descriptors, etc (with help of epoll, kqueue or select) and manages time-based callbacks. When something happens Tornado calls registered callback function.

For example, if there's incoming connection on bound socket, Tornado will trigger appropriate callback function, which will create HTTP request handler class, which will read headers from the socket and so on.

Tornado is more than just a wrapper on top of epoll - it contains own templating and authentication system, asynchronous web client, etc.

If you're not familiar with tornado, take a look at relatively short framework overview.

Tornado comes with WebSocket protocol implementation out of the box and I wrote sockjs and socket.io libraries on top of it.

As mentioned in beginning of this post, SockJS is WebSocket polyfill library, which exposes WebSocket object on client-side and sockjs-tornado exposes similar API on the server.

It is SockJS concern to pick best available transport and establish logical connection between client and server.

Here's simple chat example with help of sockjs-tornado:

class ChatConnection(sockjs.tornado.SockJSConnection):

participants = set()

def on_open(self, info):

self.broadcast(self.participants, "Someone joined.")

self.participants.add(self)

def on_message(self, message):

self.broadcast(self.participants, message)

def on_close(self):

self.participants.remove(self)

self.broadcast(self.participants, "Someone left.")For sake of example, chat does not have any internal protocol or authentication - it just broadcasts messages to all participants.

Yes, that's it. It does not matter if client does not support WebSocket transport and SockJS fill fall-back to long-polling transport - developer will write code once and sockjs-tornado abstracts protocol differences.

Logic is pretty simple as well:

- For every incoming SockJS connection, sockjs-tornado will create new instance of the connection class and call on_open

- In on_open, handler will broadcast to all chat participants that someone joined and add self to the participants set

- If something was received from the client, on_message will be called and message will be broadcasted to all participants

- If client disconnects, on_close will remove him from the set and broadcast that he left

Full example, with client side, can be found here.

Managing State

Server side session is example of state. If server needs some kind of prior data in order to process request, server is stateful.

State adds complexity - it uses memory and it makes scaling harder. For example, without shared session state, clients can only "talk" to one server in the cluster. And with shared session state - there's additional IO overhead for each transaction to fetch state from the storage for every client request.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to implement stateless Comet server. To maintain logical connection, some sort of session state is required to make sure that no data is lost in between client polls.

Depending on the task, it is possible to split stateful networking layer (Comet) from stateless business tier (actual application). In this case, business tier worker does not have to be asynchronous at all - it receives task, processes it and sends response back. And because worker is stateless, it is possible to start lots of workers in parallel to increase overall throughput of the application.

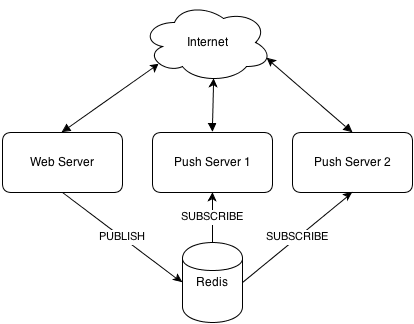

Here's how it can look, architecturally:

In this example, Redis was used as a synchronization transport and well, it is single point of failure, which is not really great from reliability perspective. Also, Redis queues were used to push requests to workers and receive answers from them.

Because networking layer is stateful, load balancer in front of application should use sticky sessions (client should go to same server every time) for realtime connections.

Integrating with WSGI applications

Obviously, it is not viable to rewrite your existing Web site to use new asynchronous framework. But it is possible to make them coexist together.

There are two ways to integrate realtime portion:

- In process

- Out of process

With Gevent, it is possible to make WSGI application coexist in same process with realtime portion. With Tornado and other callback-based frameworks, while it is possible for realtime portion to run in same process, in separate thread, it is not advised for performance reasons (due to GIL).

And again, I prefer out-of-process approach, where separate set of processes/servers are responsible for realtime portion. They might be part of one project/repository, but they always run separately, side by side.

Lets assume you have social network and want to push status updates in realtime.

Most straightforward way to accomplish this is to create separate server which will handle realtime connections and listen for notifications from main website application.

Notifications can happen either through custom REST API exposed by realtime server (works OK for small deployments), through Redis PUBLISH/SUBSCRIBE functionality (there's high chance your project already uses Redis for something), with help of ZeroMQ, using AMQP message bus (like RabbitMQ) and so on.

We'll investigate simple push broker architecture later in this post.

Structuring your code

I'll use Flask as an example, but same can be applied to any other framework (Django, Pyramid, etc).

I prefer having one repository for both Flask application and realtime portion on top of Tornado. In this case, some of the code can be reused between both projects.

For Flask, I use ordinary python libraries: SQLAlchemy, redis-py, etc. For Tornado I have to use asynchronous alternatives or use thread pool to execute long-running synchronous functions to prevent blocking its ioloop.

There are two commands in my manage.py: one to start Web application and another one to start Tornado-based realtime portion.

Lets check few use cases.

Push broker

Broker accepts messages from Flask application and forwards them to connected clients. There are lots of ready-to-use broker services (PubNub, Pusher and others or self-hosted solutions like Hookbox), but for some reasons you might want to roll out your own.

Here's dead simple push broker:

class BrokerConnection(sockjs.tornado.SockJSConnection):

participants = set()

def on_open(self, info):

self.participants.add(self)

def on_message(self, message):

pass

def on_close(self):

self.participants.remove(self)

@classmethod

def pubsub(cls, data):

msg_type, msg_chan, msg = data

if msg_type == 'message':

for c in cls.clients:

c.send(msg)

if __name__ == '__main__':

# .. initialize tornado

# .. connect to redis

# .. subscribe to key

rclient.subscribe(v.key, BrokerConnection.pubsub)Full example is here.

Brokers are stateless - they don't really store any application-specific state, so you can start as many of them as you want to keep up with increased load, as long as balancer is properly configured.

Games

Lets draft an architecture for a "typical" card game.

So, there's a table, which groups players playing same game. Table might also contain visible cards and a deck information. Each player has its internal state - list of cards on hand, as well as some authentication data.

Also, for the game, client should be a little bit smarter as there's need to have custom protocol on top of raw connection. For simplicity, we'll use custom JSON-based protocol.

Lets figure out what kind of messages we need:

- Authentication

- Error

- Room list

- Join room

- Take card

- Put card

- Leave room

Authentication message will be first message sent from the client to the server. For example, it can look like:

{"msg": "auth", "token": "[encrypted-token-in-base64]"}Payload is encrypted token, generated by Flask application. One way to generate token: get current user ID, add some random salt with time stamp and encrypt it with some symmetric algorithm (like 3DES or AES) with a shared secret. Tornado can decrypt the token, get user ID out of it and make a query to database to get any necessary information about the user.

Room list can be represented by something like:

{"msg": "room_list", "rooms": [{"name": "room1"}, {"name": "room2"}]}And so on.

On the server side, as every SockJS connection is encapsulated in instance of the class, it is possible to use self to store any player related data.

Connection class can look like (part of it):

class GameConnection(SockJSConnection):

def on_open(self, info):

self.authenticated = False

def on_message(self, data):

msg = json.loads(data)

msg_type = msg['msg']

if not self.authenticated and msg_type != 'auth':

self.send_error('authentication required')

return

if msg_type == 'auth':

self.handle_auth(msg)

return

elif msg_type == 'join_room':

# ... other handlers

pass

def handle_auth(self, msg):

user_id = decrypt_token(msg['token'])

if user_id is None:

self.send_error('invalid token')

return

self.authenticated = True

self.send_room_list()

def send_error(self, text):

self.send(json.dumps({'msg': 'error', 'text': text}))Rooms can be stored in a dictionary, where key is room ID and value is room object.

By implementing different message handlers and appropriate logic on client-side, we can have our game working, which is left as an exercise to the reader.

Games are stateful - server has to keep track of what's happening in the game. This also means that it is somewhat harder to scale them.

In example above, one server will handle all games for all connected players. But what if we want to have two servers and distribute players between them? As they don't know about each one state, players connected to the first server won't be able to play with players on the second server.

Depending on game rule complexity, it is possible to use fully connected topology - every server is connected to every other server:

In this case, game state should have required information to identify player, manage his game-related state and send game-related messages to appropriate server(s), so they can forward them to the actual clients.

While this approach works, but as asynchronous application is single-threaded, it is better to split game logic and related state into separate server application and treat realtime portion as a smart adapter between game server and the client.

So, it can work like this:

Client connects to one of realtime servers, authenticates himself, gets list of running games (through some shared state between game and realtime servers). When client wants to play in particular game, it sends request to realtime server, which then talks to the game server which hosts the game. While this looks very similar to fully-interconnected solution, servers on same tier don't interact with each other providing effective state isolation. Scaling is simple as well - add more realtime server or game servers, as their state is isolated and becomes manageable.

Also, for this task, I'd use ZeroMQ (or AMQP bus) instead of Redis, because Redis becomes single point of failure.

Game servers are not exposed to the Internet and they can be only accessed by the realtime servers.

I'd say that scaling is all about efficient state management in your distributed application.

Deployment

It is good idea to serve both Flask and Tornado portions behind the load balancer (like haproxy) or reverse caching proxy (i.e. nginx, but use newest versions with WebSocket protocol support).

There are three deployment options:

- Serve both Web and realtime portions from the same host and port and use URL-based routing to distinguish between them

- Advantages

- Everything looks consistent

- No need to worry about cross-domain scripting policies

- Usually works in environments with restrictive firewall

- Disadvantages

- Not compatible with some transparent HTTP proxies

- Advantages

- Serve Web server on port 80 and realtime portion on different port

- Advantages

- More compatible with transparent proxies

- Disadvantages

- Cross-domain scripting issues (CORS is not supported by every browser)

- Higher chance to get blocked by firewalls

- Advantages

- Serve Web server on main domain (site.com) and realtime portion on subdomain (subdomain.site.com)

- Advantages

- Possible to host realtime portion separately from main site (no need to use same load balancer)

- Disadvantages

- Cross-domain scripting issues

- Misbehaving transparent proxies

- Advantages

Real-life experience

I saw few success stories with sockjs-tornado: PlayBuildy, PythonAnywhere and some others.

But, unfortunately, I didn't use it myself for large projects.

However, I have quite interesting experience with sockjs-node - SockJS server implementation for nodejs. I implemented realtime portion for a relatively large radio station. At average, there are around 3,500 connected clients at the same time.

Most connections are short-lived and server is more than just a simple broker: it manages hierarchical subscription channels (for example radiostation-event-tweet or radiostation-artist-news-tweet) and a channel backlog. Client can subscribe to the channel and should receive all updates pushed to any of the child channels as well. Client can also request backlog - last N messages sorted by date for channel and its children. So there was a bit of logic on the server.

Overall, nodejs performance is great - 3 server processes on one physical server are able to keep up with all these clients without any sweat and there's a lot room for growth.

But there were too many problems with nodejs and/or its libraries to my taste.

After deploying to production, server started leaking memory for no apparent reason. All tools showed that heap size is constant, but RSS of the server process kept growing until process getting killed by the OS. As a quick solution, nodejs server had to be restarted every night. Issue was similar to this, but had nothing to do with SSL, as it was not used.

Upgrading to newer nodejs version helped, until process started crashing with no apparent reason and without generating coredump.

And again, upgrading to newer nodejs version helped, until V8 garbage collector started locking up in some cases and it was happening once a day. It was deadlock in V8, I found exactly same stack trace in Chromium bug tracker.

Newer nodejs version solved garbage collector issue and application is working again.

Also, callback-based programming style makes code not as clean and readable as I wanted it to be.

To sum it up - even though nodejs does its job, I had strong feeling that it is not as mature as Python. And I'd rather use Python for such task in the future, so I can be sure that if something goes wrong, it is happening because I failed and issue can be traced relatively easy.

Performance-wise, with WebSocket transport, CPython is on par with nodejs and PyPy is much faster than both. For long-polling, Tornado on PyPy is approximately 1.5-2 times slower than nodejs when used with proper asynchronous libraries. So, given current WebSocket adoption state, I'd say they're comparable.

I don't see reason to drop Python in favor of nodejs for the realtime portion.

Update (02.07.2013): TechEmpower released their round 6 of framework benchmarks and new Tornado is faster or comparable to node.js.

Final notes

While one might argue that Python is not best language to write scalable servers with. Sure, Erlang has built-in tools to write efficient and scalable applications (and there's sockjs-erlang too), but it is so much harder to find Erlang developers. Clojure and Scala are other great candidates, but Java is completely different world with own libraries, methodologies and conventions. And it is still harder to find decent Clojure developer than to find good Python guy. Go is great, but is quite young language without significant adoption.

If you already have Python experience, you can achieve decent results by continuing using Python. In most of the cases, software development is trade-off between development costs and performance. I think that Python is in good position, especially with help of PyPy.

Anyway, if you have any comments, questions or updates - feel free to contact me.

P.S. Diagrams were done in draw.io - I had to mention this excellent and free service.